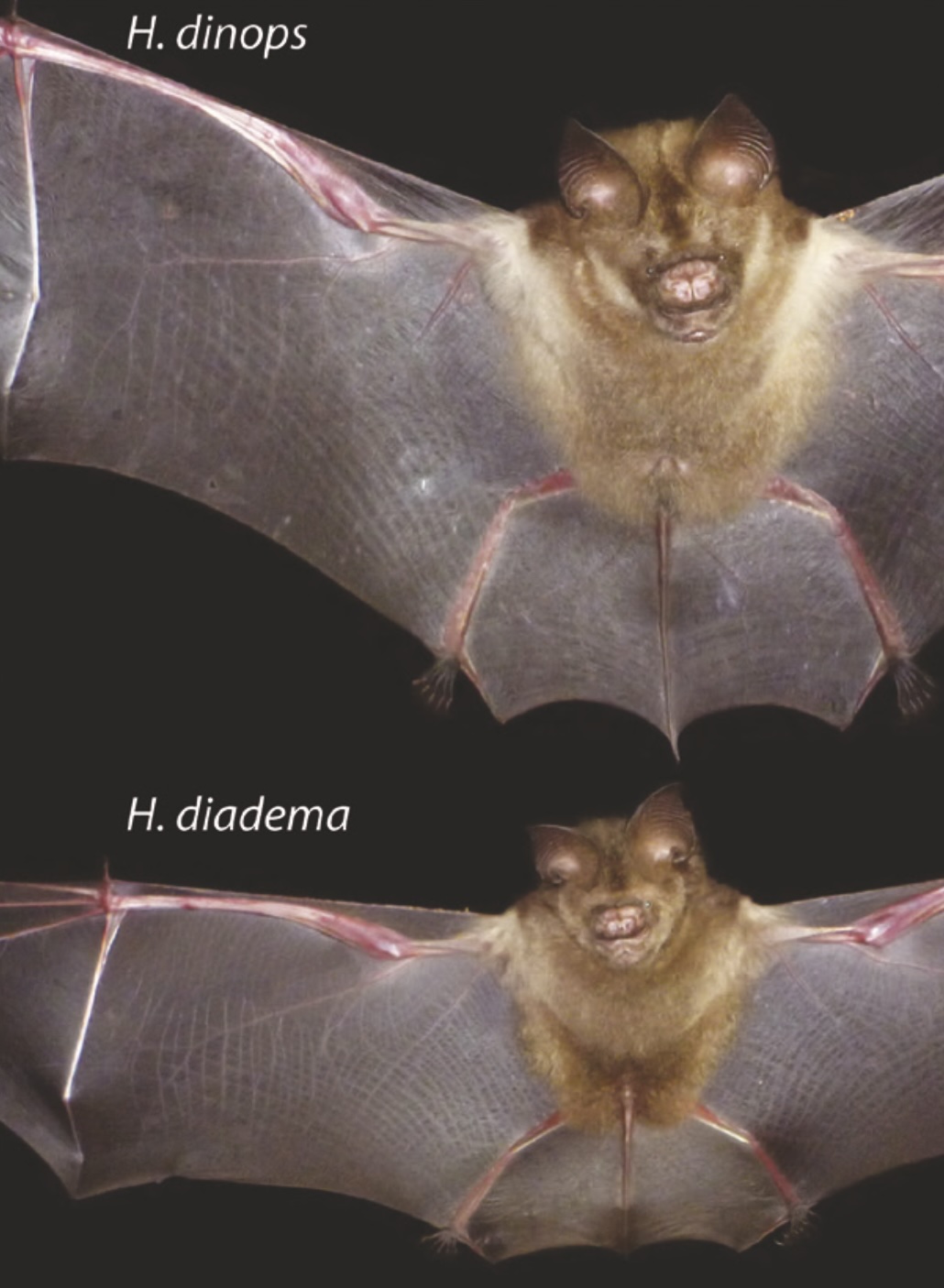

Researchers parse oddity of distantly related bats in Solomon Islands that appear identical

LAWRENCE — A study of body size in leaf-nosed bats of the Solomon Islands has revealed surprising genetic diversity among nearly indistinguishable species on different islands.

The research team behind the study from the University of Melbourne, Australia, included several evolutionary biologists from the University of Kansas — who collected specimens in the field, conducted genetic analysis and co-wrote the research appearing in the journal Evolution.

“This is genus of bats called Hipposideros with multiple species all over Southeast Asia in the Pacific,” said co-author Rob Moyle, senior curator of ornithology with the KU Biodiversity Institute and Natural History Museum, whose lab conducted much of the investigation. “In the Solomon Islands, where we've been doing a lot of fieldwork, on each island there can be four or five different species, and they parse out in terms of body size. There's a small, medium, large — or if there's more than three species, there's a small, medium, large and extra large. On one island there's five, so there's an extra small.”

According to Moyle, who also serves as professor of evolutionary biology at KU, previous generations of researchers reviewed the bats’ morphology, or physical traits, and concluded they’re one species.

“You go from one island to the next, and the medium-sized species is identical to the other islands,” he said. “Biologists have always looked at those and said, ‘OK, it's obvious. There's a small, medium and large size species distributed across multiple islands.’”

However, Moyle and his collaborators had more modern analysis at their disposal. In sequencing the DNA of bats they collected from the field (along with specimens from museum collections), the team found the large and extra large bat species weren’t actually closely related.

“That means that somehow these populations arrived at this identical body size and appearance not by being closely related — but we usually think identical-looking things are that way because they're really closely related,” Moyle said. “It brings up questions like what's unique about these islands that you’d have convergence of body size and appearance into really stable size classes on different islands.”

The team performed precise measurements on bats from different islands, confirming previous work by scientists in the Solomon Islands.

“All the large ones from different islands all clustered together in their measurements,” Moyle said. “It's not just that the earlier biologists made a mistake. They looked at them and said, ‘Oh, yeah, they're the same.’ And they're actually not. We measured them, and they're all clustered together, though they’re different species. We verified — sort of — that earlier morphological work.”

Moyle’s collaborators included lead author Tyrone Lavery of the University of Melbourne and KU’s Biodiversity Institute and Natural History Museum. Other KU co-authors include Devon DeRaad, doctoral student, and Lucas DeCicco, collections manager, both of the Biodiversity Institute and Natural History Museum; and Karen Olson of both KU and Rutgers University. They were joined by Piokera Holland of Ecological Solutions Solomon Islands; Jennifer Seddon of James Cook University and Luke Leung of the Rodent Testing Centre in Gatton, Australia.

Genetic analysis that revealed the bats weren’t closely related was performed at KU’s Genome Sequencing Core.

“When we created family trees using the bats’ DNA, we found that what we thought was just one species of large bat in the Solomon Islands was actually a case where bigger bats had evolved from the smaller species multiple times across different islands,” Lavery said. “We think these larger bats might be evolving to take advantage of prey that the smaller bats aren’t eating.”

DeRadd said the work could be “highly relevant” for conservation efforts in identifying evolutionarily significant units in this group.

“Body size had misled the taxonomy,” DeRadd said. “It turns out every island's population of extra-large bats is basically genetically unique and deserving of conservation. Understanding that is really helpful. There are issues with deforestation. If we don't know whether these populations are unique, it's hard to know whether we should be putting effort into conserving them.”

According to DeCicco, the new understanding of leaf-nosed bats was fascinating on a purely theoretical level.

“We study evolutionary processes that lead to biodiversity,” he said. “This shows nature is more complex. We humans love to try to find patterns — and researchers love to try to find rules that apply to broad suites of organisms. It's super cool when we find exceptions to these rules. These are patterns that you see duplicated over lots of different taxa on lots of different islands — a large and a small species, or two closely related species that differ somehow to partition their niches. We're seeing there are lots of different evolutionary scenarios that can produce that same pattern.”